The Robert Bateman Centre: The art snobs may sneer, but the people will come

PUBLISHED MAY 27, 2013

This article was published more than 10 years ago. Some information may no longer be current.

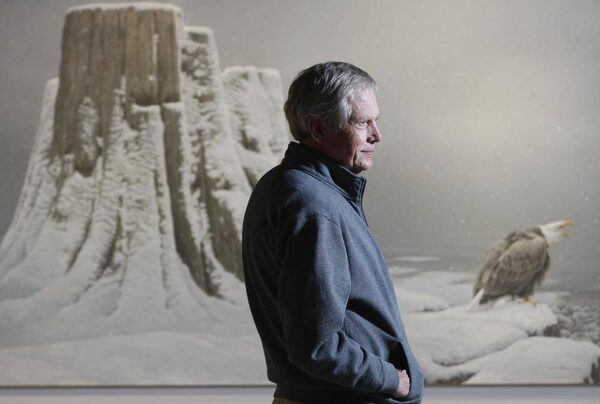

Robert Bateman is working on a painting of two whooping cranes as we talk; he likes to paint while he does interviews. Just before our conversation, he completed a large work, 122 by 152 centimetres, Lion Pride at Gol Kopje, which was en route from his studio on Salt Spring Island to the new Bateman Centre in Victoria, the paint not completely dry.

“It’s slightly tacky,” he says, then quickly clarifies: The paint he is using is oil, but quick-drying oil. “It’s tacky to the touch, not tacky to the taste.”

Some might disagree. Bateman, an internationally celebrated wildlife artist, arguably the most popular living artist in Canada and certainly among the most commercially successful – his foundation estimates there are approximately one million Bateman prints in circulation in the marketplace, plus more than one million copies of his coffee-table books – is not, to use an expression apropos of Victoria, everyone’s cup of tea. It’s hard to dispute his technical skills; the man knows how to paint a polar bear. But his remarkably realistic works of wildlife and nature have not exactly been embraced by the visual-art establishment – or, as he calls it, “the priesthood.” You’re not likely to hear his name nominated for a contemporary art award; you will not find his work in any of the country’s most prestigious public galleries.

But who needs them when you’ve got your name up on a historic building in Victoria’s Inner Harbour? The Robert Bateman Centre, showing more than 160 works and containing education facilities aimed at promoting a love of nature, opened to the public on Saturday, a day after Bateman’s 83rd birthday. Some 3,000 people checked it out over the weekend.

The centre has been years in the planning and has had a number of false starts. At one time, it appeared it might land in San Francisco; Jackson Hole, Wyo.; Burlington, Ont., or, most recently, at Victoria’s Royal Roads University a few kilometres west. But the Robert Bateman Foundation’s executive saw an opportunity to move into the old, now seismically upgraded CPR Steamship Terminal Building – formerly home to a wax museum – with the possibility of expanding into a proposed ferry-terminal development next door. For tourist traffic, you couldn’t ask for a better spot: About 1.5 million visitors stroll by each year. “This might be the first sustainable public art gallery in the country, and it’s all about location … and the fact that it’s Bateman,” says foundation president and executive director Paul Gilbert. “People want to come in; they don’t feel intimidated by [the work].”

The 1924 building is impressive. Designed by Francis Rattenbury and P.L. James, the neoclassical beauty is perched on the picturesque harbour in front of the provincial legislature and just behind Pacific Undersea Gardens. Where once you could see wax reproductions of Queen Elizabeth and Adolf Hitler, you can now see Bateman’s take on the world – in particular the wildlife of Canada and Africa.

Among the giant canvases of eagles, bears and lions, there are examples of his earlier work, dating back to 1942 when he was 12 (an elk made for his mother’s birthday), with abstracts, impressionist works and portraiture – including several of his wife Birgit Freybe Bateman through the years. A number of Freybe Bateman’s own works are installed at the entrance, which has been constructed to replicate the experience of entering their Salt Spring home.

But the bulk of the 9,000-square-foot gallery space is devoted to the subjects that have become synonymous with Bateman’s name: wildlife and nature.

It includes what is unofficially call the protest room, containing works made mostly in the late 1980s and early 1990s – Bateman’s response to what was happening to the land in areas such as Clayoquot Sound. In a rare multimedia work, a white-sided dolphin and an albatross are trapped behind a drift net. In another painting, a totem pole lies fallen in the bush and a logging truck filled with old-growth logs drives away from a clear-cut.

With concerns that his usual constituency – “the Ducks Unlimited crowd,” as Gilbert puts it – wouldn’t be on-board with these works, they’ve been seen by very few people. “It’s this cross I have to bear of niceness. I’m not actually all that nice,” Bateman says, laughing.

He does seem very nice, by the way: Even when challenged about the choice to install reproductions at the centre. About half of the 160 works here are reproductions.

“All of my other museum shows have been 100 per cent originals, but this opens up my entire body of work, which we haven’t been able to do before. …The main thing behind a piece of art is the thought.”

When asked whether he struggled with the decision, Bateman was emphatic. “I jumped in with both feet in delight because at last I for one have broken through that barrier of prejudice. I know the whole topic of Bateman and reproductions is an interesting topic in certain circles. And it’s interesting for me. I don’t think the people that oppose the idea of doing reproductions have a leg to stand on.”

He’s referring to his decision, decades ago, to mass-produce prints that he signed, leading to accusations he was flooding the market with overpriced posters rather than quality limited-edition prints.

Gilbert says the ubiquity of Bateman’s prints is the reason he decided to include reproductions (of various types) in this show.

“I’ve just run into people in all walks of life from nurses and building cleaners to senior bank executives who at some point in their life bought a Bateman print,” Gilbert says. “We have to respect the emotional relationship those people have with these reproduction prints. And the thousands of people who have that kind of relationship, they want to come here and see that we’ve treated the prints with the same kind of respect that they did.”

Michael Prokopow, a professor at OCAD University in Toronto, says while unusual, the inclusion of these reproductions is fitting since Bateman was so widely reproduced. “I only think of his work as reproductions; they were so widely disseminated and they still are. … That’s been such an important part of his practice and a characteristic of his fame and popularity.”

As for the issue of critical reception, Prokopow says one can’t argue with his success, or with the fact that he’s excluded from the critical conversation around significant cultural production in this country. “His subject matter I would say has a type of conventionality to it. You could say it’s distinguished because he’s had a long career, he exists in many major collections, he has honorary degrees. But is he a practitioner pushing that critical question of art’s responsibility to investigate and to interrogate?”

Bateman is also a respected naturalist and environmentalist who opposes the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline. He is opposed to fracking and salmon farming, but is mostly driven by a deep worry that we have become disconnected from our natural environment. Too much Nintendo and not enough nature is bad for the soul – and for society, he says.

And so, this $1.5-million centre is meant to be more than an art museum – he sees it as a gateway. There are big plans to work with school and youth groups. At the same time, the revenue generated by the gallery will help fund the foundation’s work.

Love it or sneer at it, his work clearly speaks to a mass audience. But if that’s what the art snobs think, Bateman doesn’t care.

On CBC Radio’s Q last week, taped live in Victoria, he laughed off host Jian Ghomeshi’s asking if it bugs him that he’s not in the collections of the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Gallery of Canada or the Vancouver Art Gallery. “It is the least important issue facing the planet,” Bateman said.

The next morning at the centre he was wistful, and said he had thought of a better answer. “Like Victoria, I’m too nice,” he wishes he had said. “Big-city galleries don’t like nice art. It has to have edge to it.”

Discover more from Canadian Art Junkie

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.